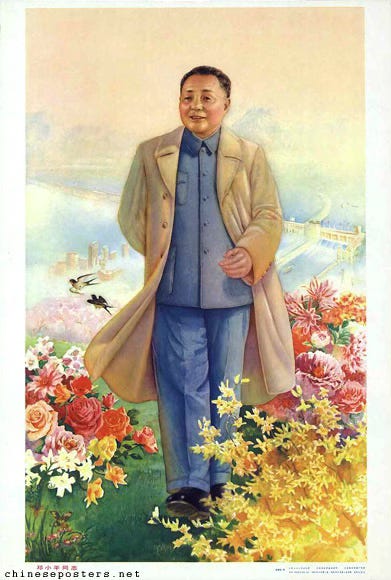

Deng Xiaoping

and the transformation of China

By Ezra Vogel

Winner of the Lionel Gelber Prize

National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist

An Economist Best Book of the Year | A Financial Times Book of the Year | A Wall Street Journal Book of the Year | A Washington Post Book of the Year | A Bloomberg News Book of the Year | An Esquire China Book of the Year…